- Research article

- Open access

- Published:

Top research priorities for preterm birth: results of a prioritisation partnership between people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 19, Article number: 528 (2019)

Abstract

Background

We report a process to identify and prioritise research questions in preterm birth that are most important to people affected by preterm birth and healthcare practitioners in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland.

Methods

Using consensus development methods established by the James Lind Alliance, unanswered research questions were identified using an online survey, a paper survey distributed in NHS preterm birth clinics and neonatal units, and through searching published systematic reviews and guidelines. Prioritisation of these questions was by online voting, with paper copies at the same NHS clinics and units, followed by a decision-making workshop of people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals.

Results

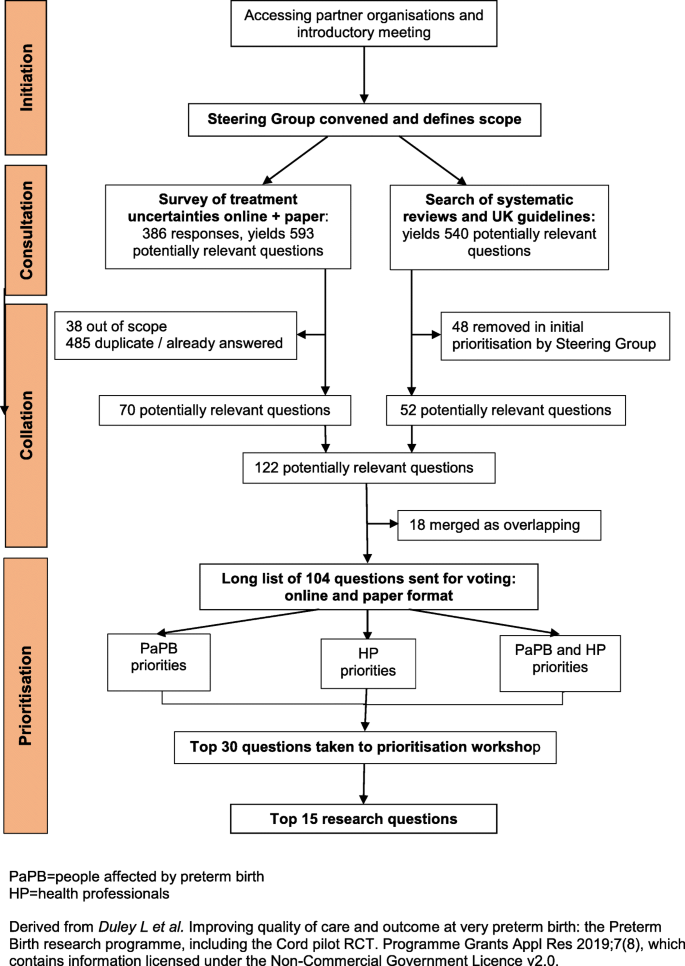

Overall 26 organisations participated. Three hundred and eighty six people responded to the survey, and 636 systematic reviews and 12 clinical guidelines were inspected for research recommendations. From this, a list of 122 uncertainties about the effects of treatment was collated: 70 from the survey, 28 from systematic reviews, and 24 from guidelines. After removing 18 duplicates, the 104 remaining questions went to a public online vote on the top 10. Five hundred and seven people voted; 231 (45%) people affected by preterm birth, 216 (43%) health professionals, and 55 (11%) affected by preterm birth who were also a health professional. Although the top priority was the same for all types of voter, there was variation in how other questions were ranked.

Following review by the Steering Group, the top 30 questions were then taken to the prioritisation workshop. A list of top 15 questions was agreed, but with some clear differences in priorities between people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

These research questions prioritised by a partnership process between service users and healthcare professionals should inform the decisions of those who plan to fund research. Priorities of people affected by preterm birth were sometimes different from those of healthcare professionals, and future priority setting partnerships should consider reporting these separately, as well as in total.

Background

Preterm birth has major impacts on survival, quality of life, psychosocial and emotional stress on the family, and costs for health services [1]. Improving outcome for these vulnerable babies and their families is a priority, and prioritising research questions is advocated as a pathway to achieve this [2, 3].

Traditionally the research agenda has been determined primarily by researchers, either in academia or industry, who have used processes for priority setting that lack transparency [4, 5]. This has contributed to a mismatch between the available research evidence and the research preferences of patients and members of the public, and of clinicians [6, 7]. Often, research does not address the questions about treatments that are of greatest importance to patients, their carers and practising clinicians [5, 8]. The James Lind Alliance has developed methods for establishing priority setting partnerships between patient organisations and clinician organisations, which then identify and prioritise treatment uncertainties in order to inform publicly funded research [9, 10]. These methods have been used for a range of health conditions [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

We report the outcomes of a process to identify and prioritise research questions in preterm birth that are most important to people affected by preterm birth and healthcare practitioners in the United Kingdom and Ireland using methods established by the James Lind Alliance [18]. This partnership differed from previous priority setting partnerships supported by the James Lind Alliance in that pregnancy is not an illness or disease, and that it involves at least two people (mother and child); in addition preterm birth can have life-long consequences for them, their families and for the health services and society. Our aim was first to identify unanswered questions about the prevention and treatment of preterm birth from people affected by preterm birth, clinicians and researchers. Then to prioritise those questions that people affected by preterm birth and clinicians agree are the most important.

Methods

The Preterm Birth Priority Setting Partnership was convened in November 2011, following an introductory meeting in July 2011. The partnership followed the four stages of the James Lind Alliance process (see Fig. 1) [9].

Initiation

Organisations whose areas of interest included preterm birth were informed about the priority setting partnership and invited to participate in, or contribute to, the introductory workshop. Those who then joined the partnership are listed in Box 1. All participating organisations were asked to complete a declaration of interests, including disclosure of relationships with the pharmaceutical or medical devices industry. Subsequently a Steering Group was convened, with members of participating organisations who volunteered to take on this role. This group was chaired by a representative from the James Lind Alliance (SC).

At the introductory workshop it was clear that many participants felt the scope of the partnership should be wider than was initially envisaged. Additional topics proposed for inclusion in the scope were uncertainties about the causes of preterm birth, about the prognosis following being born preterm, and about treatments long before birth. As widening the scope too far would risk leaving the prioritisation unachievable within a reasonable time frame and the existing resources, the Steering Group decided the scope would be restricted to uncertainties about treatments, to interventions during pregnancy and around the time of birth or shortly afterwards (taken up to the time of hospital discharge for the baby after birth).

Consultation to gather research questions (treatment uncertainties)

Research questions were gathered from people affected by preterm birth, clinicians and researchers, using methods developed by the James Lind Alliance [10]. First, a survey was distributed on-line, including through partner organisations, to ask for suggestions about preterm birth experiences, services or treatments which needed to be researched, and why the research would be important (see Additional file 1 for paper version of this survey). Respondents were asked to say if they were people with personal or family experiences of preterm birth, and/or if they were a health professional.

At an interim review of demographic data about home ownership and ethnicity from this survey there was concern that the respondents were not representative of the population at risk of preterm birth. To try and access a more high risk group, paper copies of the survey (see Additional file 1) were distributed at high risk specialist prematurity antenatal clinics at two tertiary level hospitals (University College London Hospital and Queen’s Medical Centre Nottingham), and to parents visiting their babies in three level 3 neonatal intensive care units (University College London Hospital and Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London; Liverpool Women’s Hospital) between March and December 2012. The survey closing date was extended to allow time to implement these changes. Respondents were invited to provide an email address to be notified about voting to prioritise the questions.

In addition, research questions were identified from systematic reviews of existing research and from national UK clinical guidelines (see Additional file 2).

Collation - checking and combining research questions

With support from an independent information specialist, submissions from the survey were formatted into research questions, which were checked against existing reviews and guidelines. Those already answered were removed. The remaining research questions were screened by the Steering Group, to remove those answered by a subsequent randomised trial or for which a large randomised trial was in progress, and those that were out of scope or unclear, and to combine similar research questions. This left the final long list of unanswered research questions which was sorted into similar categories, ordered chronologically from before pregnancy to hospital discharge following birth.

Prioritisation of the research questions

Prioritisation was by a two-stage process using a modified Delphi with individual voting, followed by a face-to-face workshop using nominal group technique [10]. First, the long list of unanswered research questions was made available online for public voting (from September to December 2013), with paper copies distributed to the same high risk antenatal clinics and neonatal units. Respondents were asked to pick the 10 they considered most important. Overall results and results by stakeholder group (people affected by preterm birth, health professional) were reviewed by the Steering Group to remove remaining repetition or overlap between questions. The final shortlist of 30 unanswered research questions to go forward to the prioritisation workshop was then agreed.

The aims of the prioritisation workshop were to agree a ranking for the short list, including the ‘top10’, and to consider next steps to ensure that the priorities are taken forward for research funding. Participants were invited from across the partnership, and included representatives from organisations representing both people affected by preterm birth and clinicians, parents of babies born preterm, and adults who were born preterm. Prior to the workshop, participants were sent the shortlist of unanswered research questions.

At the workshop (held in January 2014), after an introductory session participants were assigned to one of four small groups, each with a facilitator, to discuss ranking for each uncertainty. Groups were pre-specified in advance to include a mix of parents, people born preterm, clinicians and other health professionals. The groups were provided with a set of 30 large cards, each printed with one shortlisted research question. On the reverse were examples of wording from the original submissions, and a breakdown of how people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals had scored that question in their voting. Following discussion, these cards were placed in ranked order. Over the lunchtime break, rankings from the four groups were aggregated into a single ranking order. These aggregate rankings were presented at a plenary session, to demonstrate where there was existing consensus between groups, and where there were differences. Participants were then reconvened into three small groups, again pre-planned so each had a new mix of participants and retained a balance of backgrounds, to discuss the aggregate ranking. Similar processes were used as in the earlier small groups, with the aim of agreeing the top ten research questions and ranking all 30 questions. Aggregated ranking from the three small groups was taken to a final plenary session, with the 30 cards laid out on the floor in ranked order. Participants then debated and agreed the final ranking.

Results

Forty two organisations were approached and invited to participate in the priority setting partnership (see Additional file 4); of these 25 accepted and joined the partnership (see Table 1). Ten organisations were represented on the Steering Group; four representing those affected by preterm birth, and six representing health professionals (obstetricians and neonatologists). Some Steering Group members were parents of infants born preterm, or had themselves been born preterm. The group also included four non-voting members: two researchers who co-ordinated the prioritisation partnership, one a clinical academic with a background in obstetrics and the other with expertise in public engagement in research; one charity representative, and one PhD student.

When the online survey closed it had been accessed by 1076 people, and completed by 349; an additional 37 paper survey forms were completed and returned. Hence a total of 386 people responded of whom 204 (53%) said that they were affected by preterm birth, 107 (28%) that they were health professionals, 43 (11%) that they were both affected by preterm birth and a health care professional, and 32 (8%) did not answer this question (Table 2). Of the 247 respondents affected by preterm birth, most 186 (75%) reported they were parents of a preterm baby, but some were grandparents and other family members.

The 386 responses contained 593 potential research questions. Submissions were formatted into research questions, with similar submission combined into one question (see Additional file 5), and screened to remove those already answered, out of scope or unclear, (see Additional file 6). Thirty eight submissions were removed as being outside the scope of this process. After merging similar questions and removing those that were fully answered, 70 unanswered questions were left from the survey.

The search of systematic reviews and clinical guidelines identified 540 potentially relevant questions. As there was such a large number, the Steering Group agreed a process to prioritise which would go forward to the next stage. Each member was asked to select the 60 questions from systematic reviews they considered to be most relevant and important. They then brought their list of 60 to a face-to-face meeting at which questions were only considered as potential priorities for the voting stage if they were supported by three or more members. This resulted in 28 questions from systematic reviews and 24 from clinical guidelines remaining in the process. Overall there were then 122 questions; as 18 of these overlapped with other questions, they were merged to give a final ‘long list’ of 104 unanswered research questions (see Additional file 3).

The 104 questions on the long list were sent for an online public vote, with paper copies distributed to the same high risk antenatal clinics and neonatal units. Overall 507 people voted (448 online and 59 on paper); 231 (45%) said they had been affected by preterm birth, 216 (43%) that they were a health professional, and 55 (11%) that they were affected by preterm birth and also a health professional (Table 2). Type of respondent was not known for 5 (1%) voters. Of the 271 who said they were a health professional (including those who had been affected by preterm birth themselves), 85 said they were an obstetrician, 51 a nurse, 44 a neonatologist, 24 a midwife, 4 a general practitioner, 32 were other health professionals and 31 preferred not to say. Of those who voted, 512 (87%) reported their ethnicity as white, and ethnicity was not known for 8 (2%). Responses were received from the four nations within the United Kingdom, and from the Republic of Ireland.

For public voting, the top priority (which treatments (including diagnostic tests) are most effective to predict or prevent preterm birth?) was the same for all three types of respondent (Table 3), but there was considerable variation in how other questions were ranked. Several questions were in the overall top 10 for only one type of voter. Questions ranked 1–40 in the public vote were reviewed by the Steering Group, taking into account the voting preferences of people affected by preterm birth and the overall balance of the topics. Four questions were removed: one had already been answered, one was being addressed by an ongoing trial, and two were merged with another broader question (all three being about infant feeding). A shortlist of the top 30 questions was then taken forward to the prioritisation workshop (Table 4).

The workshop to prioritise these 30 questions was attended by 34 participants; 13 parents or adults who had been born preterm and 21 health professions (neonatology, obstetrics, midwifery, speech therapy and psychology). Several of the health professionals also had personal experience of preterm birth. In addition, there were four facilitators (two from the James Lind Alliance and two non-voting members of the Steering Group), five observers (one from the James Lind Alliance, one from a research funding organisation in Canada, one from the Institute of Education University of London, and two who were non-voting members of the Steering Group).

During the prioritisation workshop, two questions were merged as it was agreed they overlapped, and the wording of a few others was modified for clarification. Following the first round of small group discussion, there was considerable variation in the top priorities between the four groups. Following the second round of small group discussion there was agreement about the top few priorities. During the final plenary discussion about the aggregated ranking there was consensus about the top seven questions, less consensus about the next three, and disagreement about those ranked as between 10 and 20. As it was not possible to achieve consensus about the top 10 questions within the timeframe, a proposal to expand this to a top 15 was agreed. Consensus about the top 15 was then achieved (Table 4). This top 15 had some significant differences to the ranking following public voting. The most noticeable was two questions ranked 18 (How do stress, trauma and physical workload contribute to the risk of preterm birth, are there effective ways to reduce those risks and does modifying those risks alter outcome?) and 26 (What treatments can predict reliably the likelihood of subsequent infants being preterm?) at the workshop were ranked 3 and 4 respectively in the overall public vote, and 2 and 3 by service users in the public vote (Table 3).

Discussion

The unanswered research questions relevant to preterm birth identified during this process were prioritised in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland by people affected by preterm birth (parents, grandparents, adults who were born preterm, and others affected by preterm birth), by a range of health professionals, and by people who were both personally affected by preterm birth and a health professional. To our knowledge this is the first such process in preterm birth. People affected by preterm birth and health professionals had many shared priorities, but our process demonstrates that on some questions they have different perspectives. Priorities may also change over time and in different settings, Hence, although the top research priorities from this process should be considered by those who plan and fund research in this area, the full list of 104 unanswered questions is also relevant to decision-making about research funding. This is particularly true if we wish to make research more relevant to those whose lives have been affected by preterm birth, and the healthcare workers who care for them.

While several of the top priorities for research are broad topics already well recognised as important, such as what is the optimum milk feeding regimen for preterm infants and prevention of infection, others are indicative of areas previously underrepresented in research; for example packages of care to support families after discharge, and what is the role of stress, trauma and physical workload in the risk of preterm birth, and are there effective ways to reduce this risk and does this influence outcome. This is in keeping with findings from previous James Lind Alliance partnerships, which suggests and highlights the value of partnership and shared decision making with an inclusive stakeholder group with balanced representation of service users and clinicians [7].

In line with the literature on consensus development [19], the strengths of this Preterm Birth Priority Setting Partnership include the large numbers of participants in the process, the range of stakeholders involved, the formality of the processes, the use of facilitators for face-to-face debate to ensure that all options were discussed and all participants had a chance to voice their views, providing feedback and repeating the judgment, and ensuring that judgements were made confidentially. The first three features applied to both the consultation and the workshop; the last applied only to the consultation. The change in priorities between the survey and the workshop deserves further investigation. Although the choice of individuals within the professional groups represented is unlikely to have made a difference to the priorities, [20] difference in status across workshop participants may have [19].

Preterm birth is associated with factors such as lower socio-economic status, ethnicity (such as African origin), and maternal age (being lower than 18 years or above 35 years) [21]. Despite implementing strategies to reach a more representative population, our respondents remained primarily white and with a relatively high proportion of homeowners, hence not representative of the population affected by preterm birth. This could limit generalisablity of these priorities to other populations. A wide range of relevant health professionals participated in the public voting, including neonatologists, obstetricians, neonatal nurses, midwives, speech and language therapists, psychologists and general practitioners; strengthening generalisablity.

Maintaining balanced representation between people affected by preterm birth and the different groups of health professionals for the final prioritisation workshop was challenging. This may have had implications for the final decisions, as happens in guideline development, where consensus development research concludes that differences in how groups are constituted (but not individual members) leads to different decisions [22]. At our workshop differences in priorities between the various professional groups contributed to the difficulty in achieving consensus for a top 10 list, and to the two ‘lost priorities’ which although ranked in the top 5 at the public vote were not included in the final top 15. The difficulty in agreeing a top 10 underlines the complexity of priority setting for research, particularly for topics such as preterm birth, which involve mother and baby, as well as their wider family. This complexity, and the differing priorities of different stakeholders, make it important to publicise the top 30 list, and the full long list of 104 questions, as well as the top 15 priorities [23].

Large changes in ranking following the public vote and the final prioritisation appeared to be related to difficulty in the perspective of people affected by preterm birth being heard in the large group session, and an imbalance between the different priorities of two key types of health professional (neonatologists and obstetricians). This was further complicated by fewer obstetricians than expected attending the workshop, and by some of the healthcare professionals also being researchers. Another element of our work, reported in detail elsewhere, was a nested observational study of how service users and healthcare professionals interact when making collective decisions about research priorities [24]. This suggested that health care professionals and service users tended to use different pathways for persuasion in a group discussion, and communication patterns depended on the stage of group development. The Steering Group had worked together for some time, and when new participants joined for the workshop communication patterns returned to an earlier stage. This may have influenced quality of the consensus.

Reporting of the process for prioritisation is therefore important for transparency, and to identify ways to improve it. Future prioritisation processes, particularly those with a similar wide range of healthcare professionals, should endeavour to anticipate potential different perspectives and mitigate any imbalance where possible, and should report voting separately by ‘service users’ and healthcare professionals. Similarly, whilst it may be appropriate to include healthcare professionals who are also researchers in prioritisation, this potential conflict of interest should be declared and taken into account.

This priority setting was limited to the United Kingdom and Ireland, and is therefore most readily generalisable to settings with a similar population and health system. Previous research prioritisation processes for preterm birth [3, 25] did not include people affected by preterm birth and were for low and middle income settings. The most recent neonatal prioritisation exercise in the UK did not include people affected by preterm birth and considered only medicines for neonates [26]. Although unanswered research questions are universal, prioritisation of these questions depends on the local values, context and setting. Nevertheless, there are common priorities across these different settings and our prioritisation process in the UK, such as prevention of preterm birth, postnatal infection and lung damage.

Failure to take account of the views of users of research (i.e. clinicians and the patients who look to them for help) contributes to research waste [27]. James Lind Alliance priority setting partnerships brings together ‘patients, carers and clinicians’ to identify unanswered research questions and to agree a list of the top priorities, (http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/about-the-james-lind-alliance/about-psps.htm) which can then shape the health research agenda [12,13,14]. The aim is to ensure that those who fund health research, and also those who support and conduct research, are aware of what really matters to both patients and clinicians. In our priority setting partnership, people affected by preterm birth and the different groups of health care professionals had different priorities. This underlines the importance of this paper presenting the full list of 30 questions taken forward to the prioritisation workshop, and the respective priorities of people affected by preterm birth and health professionals, as well as the long list of 104 unanswered questions sent out for public voting.

Conclusions

We present the top 30 unanswered research questions identified and prioritised by the priority setting partnership, along with the full list of 104 questions. These include treatment and prevention as well as how care should be organised and staff training. They should be publicised to the public, to research funders and commissioners, and to those who support and conduct research.

People affected by preterm birth and health professionals sometimes had different priorities. Future priority setting partnerships should consider reporting the priorities of service users and healthcare professionals separately, as well as in total. Those with a wide range of healthcare professionals involved should anticipate potential different perspectives and mitigate any imbalance where possible. Healthcare professionals who are also researchers should declare this potential conflict before participating in prioritisation, so that it can be taken into account.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):261–9.

Delivering action on preterm births. Lancet. 2013;382(9905):1610.

Lackritz EM, Wilson CB, Guttmacher AE, Howse JL, Engmann CM, Rubens CE, Mason EM, Muglia LJ, Gravett MG, Goldenberg RL, et al. A solution pathway for preterm birth: accelerating a priority research agenda. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e328–30.

Chalmers I. The perinatal research agenda: whose priorities? Birth. 1991;18(3):137–41 discussion 142-135.

Chalmers I. Well informed uncertainties about the effects of treatments: how should clinicians and patients respond? BMJ. 2004;328:475–6.

Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet. 2000;355(9220):2037–40.

Crowe S, Fenton M, Hall M, Cowan K, Chalmers I. Patients’, clinicians’ and the research communities’ priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch. BMC Res Involve Engage. 2015;1:2.

Partridge N, Scadding J. The James Lind Alliance: patients and clinicians should jointly identify their priorities for clinical trials. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1923–4.

Cowan K, Oliver S. The James Lind Alliance guidebook: James Lind Alliance; 2012. http://www.jlaguidebook.org/

The James Lind Alliance Guidebook. Version 8 2018 [http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/jla-guidebook/]. Accessed Dec 2019.

Fernandez MA, Arnel L, Gould J, McGibbon A, Grant R, Bell P, White S, Baxter M, Griffin X, Chesser T, et al. Research priorities in fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis: a UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e023301.

Kelly S, Lafortune L, Hart N, Cowan K, Fenton M, Brayne C, On behalf of the Dementia Priority Setting, Partnership. Dementia priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance: using patient and public involvement and the evidence base to inform the research agenda. Age Ageing. 2015;44(6):985–93.

Layton A, Eady EA, Peat M, Whitehouse H, Levell N, Ridd M, Cowdell F, Patel M, Andrews S, Oxnard C, et al. Identifying acne treatment uncertainties via a James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7):e008085.

Deane KH, Flaherty H, Daley DJ, Pascoe R, Penhale B, Clarke CE, Sackley C, Storey S. Priority setting partnership to identify the top 10 research priorities for the management of Parkinson's disease. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006434.

Hollis C, Sampson S, Simons L, Davies EB, Churchill R, Betton V, Butler D, Chapman K, Easton K, Gronlund TA, et al. Identifying research priorities for digital technology in mental health care: results of the James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(10):845–54.

Pollock A, St George B, Fenton M, Firkins L. Top ten research priorities relating to life after stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(3):209.

Horne AW, Saunders PTK, Abokhrais IM, Hogg L, Endometriosis Priority Setting Partnership Steering G. Top ten endometriosis research priorities in the UK and Ireland. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2191–2.

Perlman JM, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, Atkins DL, Chameides L, Goldsmith JP, Guinsburg R, Hazinski MF, Morley C, Richmond S, et al. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):e1319–44.

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, Askham J, Marteau T. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(3):i-iv):1–88.

Hutchings A, Raine R. A systematic review of factors affecting the judgments produced by formal consensus development methods in health care. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11(3):172–9.

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84.

Hutchings A, Raine R, Sanderson C, Black N. A comparison of formal consensus methods used for developing clinical guidelines. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11(4):218–24.

Duley L, Uhm S, Oliver S, on behalf of the Steering Group. Top 15 UK research priorities for preterm birth. Lancet. 2014;383(9934):2041–2.

Duley L, Dorling J, Ayers S, et al. Improving quality of care and outcome at very preterm birth: the Preterm Birth research programme, including the Cord pilot RCT. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019 Sep. (Programme Grants for Applied Research, No. 7.8.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547087/. https://doi.org/10.3310/pgfar07080.

Bahl R, Martines J, Bhandari N, Biloglav Z, Edmond K, Iyengar S, Kramer M, Lawn JE, Manandhar DS, Mori R, et al. Setting research priorities to reduce global mortality from preterm birth and low birth weight by 2015. J Glob Health. 2012;2(1):010403.

Turner MA, Lewis S, Hawcutt DB, Field D. Prioritising neonatal medicines research: UK medicines for children research network scoping survey. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:50.

Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gulmezoglu AM, Howells DW, Ioannidis JP, Oliver S. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):156–65.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to all the organisations which contributed to the partnership, to all the people who responded to our survey and voting, and to the participants in the final workshop. Thanks also to Ann Daly, Drew Davy, Elizabeth Oliver and Claire Stansfield for their help with the systematic reviews.

Funding

This paper presents work funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP-PG- 0609-10107). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. ALD is supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. During this work CG was funded by the NIHR as a Clinical Lecturer and an Academy of Medical Sciences Starter Grant for Clinical Lecturers, supported by the Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, British Heart Foundation, Arthritis Research UK, Prostate Cancer UK and The Royal College of Physicians.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were members of the Steering Group, and so planned the study, and reviewed data. SC chaired the Steering Group, and the final workshop. SU conducted the survey, managed the voting, and analysed the data. LD drafted the paper, with feedback from all authors. All authors agree the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research Ethics Committee approval for the whole priority setting exercise was obtained from the Institute of Education, University of London (reference FCL 318), and for distribution of paper versions of the survey and voting was from the North Wales REC (Central & East) Research Ethics Committee (reference 12/WA/0286). Forms for both the survey of uncertainties and voting were self-completed, and consent was assumed if the form was completed and submitted (online) or returned (paper version). Consent for public surveys of this type of was not required by the NHS research ethics committees. For the nested qualitative study, consent to sound record meetings was given verbally by members of the steering group and the workshop participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Survey form.

Additional file 2.

Mapping systematic reviews.

Additional file 3.

Long list of questions sent for voting.

Additional file 4.

Organisations invited to participate.

Additional file 5.

Submissions formatted as research questions.

Additional file 6.

Reasons for excluding submissions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Oliver, S., Uhm, S., Duley, L. et al. Top research priorities for preterm birth: results of a prioritisation partnership between people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 528 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2654-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2654-3